Stepping along the frozen banks of the Ukika River, I walk a trail through a southern beech evergreen forest whose branches are sprinkled with groups of orange fungi, each round and plump as a golf ball. The trees are worlds in miniature, covered in small bryophytes—mosses, liverworts, and hornworts—and adorned with feathery lichen named old man’s beard, which streams by as I walk. Twisted roots and fallen logs crisscross the trail, while the howling wind makes the canopy groan ominously. I’m completely alone, except for the occasional rhythmic tapping of a Magellanic woodpecker somewhere above, its bright red head hidden among the leaves.

Before long, I leave Parque Municipal Ukika and observe the river cutting through a rocky beach to empty into the steel-gray Beagle Channel, a serpentine body of water that sews the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans together along Tierra del Fuego. In my foreground is Villa Ukika, a village inhabited by a small Indigenous Yahgan group; in my background, the outskirts of Puerto Williams, the world’s southernmost city.

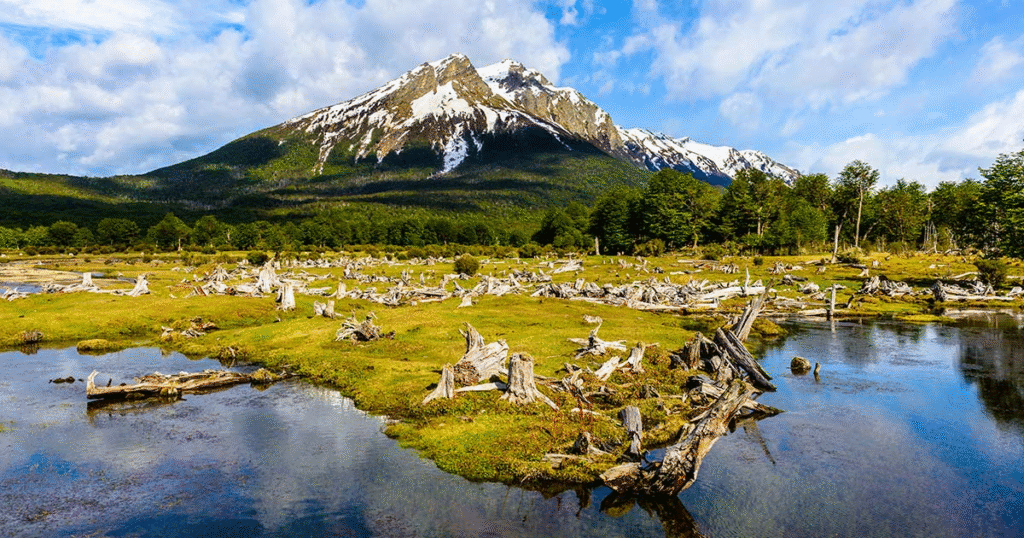

Under Patagonia, South America breaks up into an island, inlet, and peninsula maze, carved apart by writhing rivers and covered in dark green forests and glinting glaciers. Tierra del Fuego—Land of Fire. This harsh terrain was formed by a youth named Táyin, according to the oral histories of the Indigenous Selk’nam, “grabbing stones and shooting them in every direction with his slingshot. Where they struck, huge fissures opened up in the ground and filled with water.”

The area’s poetic name derives from the Selk’nam’s bonfires, seen by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1520 during his ill-fated effort to circumnavigate the globe. Half a millennium later, this thinly inhabited wilderness, divided between Argentina and Chile, is still untrammeled. Yet increasingly, tourists are flocking to Ushuaia, formerly a penal colony that earned the nickname “Siberia of the South” and today Tierra del Fuego’s largest city—largely as a starting point for Antarctic cruises.

But relatively few go on south over the Beagle Channel (so called because it was the name of the ship on which a young Charles Darwin made his famous journey) to Chile’s Navarino Island, where Puerto Williams is located. In 2019, the government in Chile elevated this 2,800-resident colony to city status—although it remains 1,500 miles from Santiago and a paltry 670 miles from Antarctica.

You need a plane or a boat to get to Puerto Williams, and remoteness is what makes it beautiful. During my first visit, before the pandemic, I did it the hard way: a bus from Punta Arenas, a ferry ride over the turbulent Strait of Magellan to Isla Grande, and then a 12-hour ride through Argentina’s half of Tierra del Fuego to Ushuaia. I traveled the next day by boat across the Beagle Channel, through raucous sea lion colonies sprawling over rocky islets, to disembark at Puerto Navarino and board a minibus for Puerto Williams.

This time, I take the shortcut—a 30-minute flight from Punta Arenas with stunning vistas of snow-capped Alberto de Agostini National Park. The region once captivated Darwin, who in The Voyage of the Beagle described breaching whales, intense storms, and “magnificent glaciers extending from the mountain side to the water’s edge. It is scarcely possible to imagine anything more beautiful than the beryl-like blue of these glaciers.”

Situated on the south shore of the Beagle Channel, under the mountainous slopes and rocky spires of the Dientes de Navarino range, Puerto Williams is officially Chile’s Antarctic Province capital but has the ambiance of a small town. It was founded as a naval base during the 1950s in Yahgan land and boasts a neat military housing area (accommodating roughly half the town) plus assorted civilian houses with satellite dishes, piles of firewood, and shaggy dogs.

I walk the deserted, wind-swept streets under a late-afternoon sun, passing wooden churches, town hall buildings, a schoolhouse, a couple of shuttered stores, and guesthouses. Cows and horses graze on daisy-covered fields, and front doors remain unlocked—crime is virtually unknown here. I stop on a boardwalk facing the channel to see a storm petrel circle over fishing boats pulling in giant king crabs.

Following the delight of the crab at a sailor-themed restaurant, I speak with Anna Baldinger of Hotel Fio Fio, where I am lodging. From Austria by birth, she had come to teach but fell in love with the island and a boy. “Puerto Williams is like a bubble—people nickname it the village at the end of the world,” she says.

Although the city is a mere 70 years old, Yahgan people have inhabited the place for millennia, as evidenced in the archaeological sites scattered about the island. Anthropologist Maurice Van de Maele, proprietor of Hotel Fio Fio, informs me Navarino boasts one of the world’s highest concentrations of ancient sites—perhaps 2,000, such as middens (ancient trash heaps) and circular depressions of old shelters, several of which are visible on the drive from Puerto Navarino.

Maurice, a past director of the town’s museum (currently named Museo Territorial Yagan Usi – Martín González Calderón in respect of Indigenous heritage), tours me around such artifacts as bone harpoons, delicate jewelry, and canoes within the beautiful building, which has a sun-dried whale skeleton on the exterior. The museum also explains the destruction inflicted on Indigenous people during 19th- and 20th-century colonization, when missionaries, gold rush miners, and ranchers poured into the area.

Although Tierra del Fuego seems eternal, the inevitable is on the horizon. In my time there, I notice just a few tourists—hikers, birders, fishermen, or passersby looking for “the end of the world.” But Antarctic cruise ships visit increasingly often, spewing forth hundreds of visitors clad in identical jackets, often pursuing guided tours, and plans are underway for a new dock to accommodate larger ships. Plans for a large hotel and airport improvements are also afoot.

Road projects are also spreading throughout Tierra del Fuego. The southernmost road in Chile, the Y-905, today terminates just north of Villa Ukika, but plans call for its extension to Puerto Toro, the globe’s southernmost established settlement. The new Sub-Antarctic research center at Cape Horn, set atop a ridge, resembles a high-tech spaceship with its windmill.

But as I walk west from Puerto Williams, concerns about overdevelopment disappear. The path up 2,000-foot Cerro Bandera—the first section of the legendary 33-mile Dientes de Navarino circuit—climbs tightly through beech trees before thining to a wind-blasted tundra. At the summit, a Chilean flag flails in the gale, and the horizon expands over the Beagle Channel, the serrated Dientes summits, and a glacial lake embraced by snow-dusted peaks.

My fingers are numb, and freezing sleet bites at my face, but I just can’t help smiling, recalling Anna’s words: “When you stand atop Cerro Bandera’s peak, no one is in front of you. The rest of the world is far, far away.”