The defining natural feature of Capitol Reef is the Waterpocket Fold. Stretching for a hundred miles, its parallel ridges rise from the desert like enormous ocean waves rolling toward land. Over time, the exposed edges of this uplift have worn away, leaving behind a rugged landscape of massive domes, sheer cliffs, and a labyrinth of winding canyons.

To geologists, the fold is one of the biggest and most visible monoclines in North America. To visitors, it’s a place of breathtaking beauty and peaceful solitude—so far removed from civilization that the closest traffic light is 78 miles away. And even though it’s off the main path, covering 378 square miles of remote terrain, the park still draws close to 750,000 people every year.

The name “Capitol Reef” comes from a particularly vibrant section of the fold where rounded Navajo sandstone forms dome-like shapes resembling capitol buildings, while steep cliffs create a natural barrier—often called a “reef.” Though a highway now cuts through this “reef,” exploring the park’s more secluded areas remains a challenge.

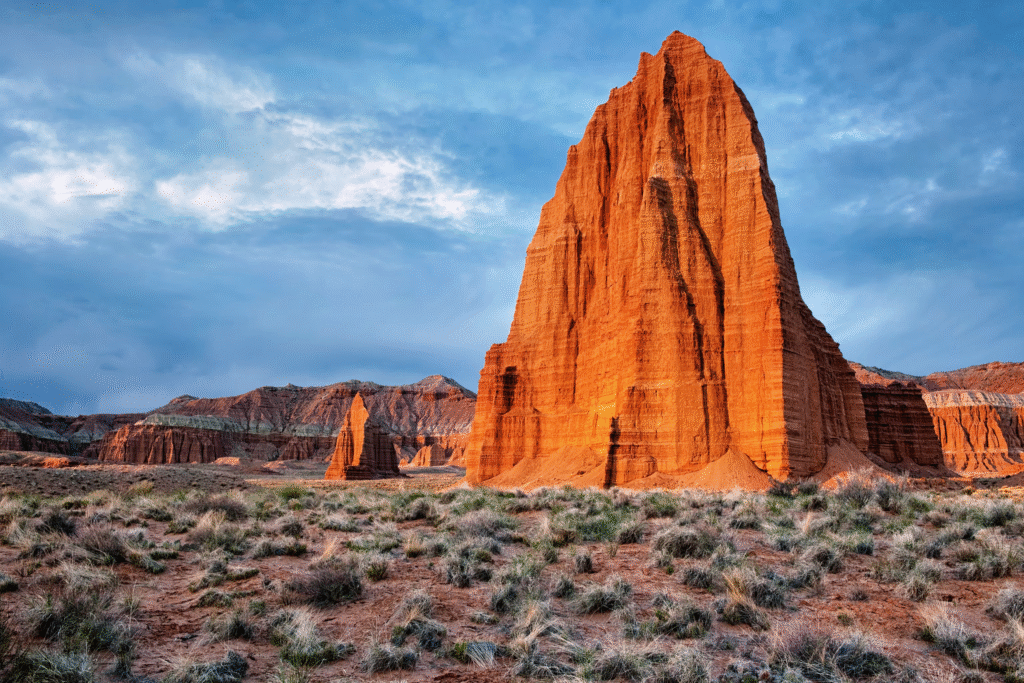

At the southern end of the fold, Lower Muley Twist Canyon and Halls Creek Narrows offer fantastic wilderness backpacking. Up north, along the park’s border, lies Cathedral Valley—a place of quiet isolation where jagged monoliths tower hundreds of feet high.

But the most famous part is the middle section. Here, the stark beauty of towering cliffs contrasts with the lush oasis created by 19th-century Mormon pioneers along the Fremont River, where they founded the village of Fruita. Their old irrigation channels still nourish fruit trees in fields abandoned by Fremont Indians 700 years ago. Nowadays, mule deer graze on orchard grasses and alfalfa, while visitors pick apples, peaches, and apricots.

One of the most striking traces of the Fremont culture is their intricate rock art. Many petroglyph panels are crowded with figures resembling bighorn sheep. The last native desert bighorn—a unique subspecies—was spotted in the park back in 1948. Their disappearance was due to overhunting and diseases spread by domestic sheep. The Park Service brought them back in 1984, 1996, and 1997, and these herds have managed to survive.

How to Get There

From Green River (about 85 miles away), take I-70 to Utah 24, which leads to the east entrance. For a more scenic route, start at Bryce Canyon National Park, follow Utah 12 over Boulder Mountain, then take Utah 24 just outside the park’s west entrance. Nearest airport: Salt Lake City.

When to Go

The park is open year-round. Spring and fall are mild and perfect for hiking. Winters are cold but short. Some back roads can get blocked during spring thaw, summer rains, or higher-elevation winter snows.

How to Visit

If you only have one day, drive Utah 24 along the Fremont River, then take the Scenic Drive through the park’s heart—this area has nearly 40 miles of well-maintained trails for great hikes. For a second day, try parts of the Burr Trail Loop with a walk to Strike Valley Overlook. If you’re staying longer, explore the Cathedral Valley Loop or hike deeper into the Waterpocket Fold’s remote canyons. Always check road, trail, and weather conditions before heading out.